Beyond Realism: The Drawings and Paintings of Antonio Lopez Garcia

By: Roberto Rosenman

Realism has been a problematic style in the 20th century. Considered by many as bourgeois, passé, and incapable of engaging contemporary issues, it has often been relegated to the sphere of the academic art. For many years, this was the case for Antonio Lopez Garcia who, in spite of being called by critic Robert Hughes as “the greatest realist artist alive”1, has until recently received little attention until outside of his native Spain.

One of the main reasons for this is that Lopez’s work cannot be defined in conventional terms. For one, he works simultaneously in drawing, painting and sculpture, all of which have undergone many stylistic changes throughout his career. Attempts by critics to link Lopez and the Madrid realists to other neo-realist schools have proven ineffective as their methods, models, and motivations have been uniquely different. Even an attempt to explain ‘Madrid realism’ has been difficult as the group and its core members (a mere five) seem to share an allegiance founded on friendship, family, and a common history, rather than a defined aesthetic approach.

Equally misleading is trying to place Lopez within a historical Spanish framework. His name often appears alongside Velazquez and El Greco (a 2009 exhibit at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts coincided with an exhibition on these two painters) but Lopez himself has been reluctant to cite them as sources. We do know that while Lopez was absent from the international art world, he was also marginalized for the greater part of his career in his native Spain when the avant-garde took precedence over representational art. This marginalized position is important as it shows that Lopez has always been an uncompromising painter who has never been propelled by current trends or neo-classicism. This is key to understanding his work as it figures both in his themes and the method in which he works.

When we examine Lopez-Garcia’s work over the last five decades, we can begin to see some common themes running through his seemingly different work. First there is, through his choice of subject matter, a desire to depict aspects of everyday existence. Secondly, we encounter a pre-occupation with multiple plains of reality. This is expressed through a tension of opposites: chaos and order, modernization and decay, and the world of the infinite and the familiar. Lastly, there is the temporality of time or what Gilles Aillaud calls ‘The eternity of the ephemeral”, a theme which Lopez expresses in his work through an exploration of light. He is known for spending up to 7 years on a painting, most of which is waiting for a specific position of the sun. By painting at dawn or dusk, he attempts to depict what is fleeting in nature. At the same time, when painting from nature, Lopez is committed to recording the fluctuations of his subject matter, adjusting his work throughout it’s creation to mimic the constant state of flux of his subject matter.

Two recent retrospectives of his work at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, along with the recent sale of his painting Madrid desde Tores Blancas for a record breaking 1.7 million Euros at Christies London have solidified his reputation as one of the most unique and important contemporary painters. Only recently have scholars begun to re-examine his work, recognizing him as an entirely unique painter who is redefining the genre of realism by unhinging it from its classical and academic roots.

From La Mancha to Madrid

Lopez-Garcia was born in 1936 in the town of Tomelloso in Spain to a farming family and first studied under his uncle, a local landscape painter. Recognizing drawing skills in the boy, Lopez-Garcia was sent to attend the Escuela Superior de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid at the age of 13.

The sense of isolation that often accompanies migration was doubled with the social isolation in which he found himself on trying to establish himself in the art world of Madrid. During the mid 1950’s, non-objective painting dominated Europe and America and realist painting was considered bourgeois and passé beside new models like abstract expressionism. While a student in the Escuela de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Lopez began to meet other students who also shared an interest in realism: Isabel Quintanilla, the sculptor Julio Lopez Hernandez and his brother Francisco, and Lopez’s future wife, Maria Moreno. They would later be known as the Madrid realists, exhibiting together and creating family ties. Yet compared to the avant-garde groups which arose during this time: the ‘Dau al Set’ (which included Anoni Tapies) and later ‘El Paso’, the Madrid realists seemed united more by their rejection of abstract models rather than any defined aesthetic criteria. They produced no manifesto and rarely ventured outside their native Spain. The emergence of a realist movement within the environment of the avant-garde is nothing new in the history of art. We can look for example to the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) artists who emerged quite separate from German Expressionism and called for a return to classical models and we see this trend repeated again in the 1960’s where the Hyper-Realist movement would emerge almost inseparably from Pop-Art. As in the case of the Madrid Realists, these movements seemed to call for a ‘return to order’ amidst turbulent times.

Though the Madrid realists did manage to find their place beside abstract work in Madrid, exhibiting together as early as 1955, Lopez and his circle were for the most part marginalized in Spain and abroad. Foreign investment and tourism also helped transform Spain into a modern, urbanized nation; an image which the Franco government was eager to promote. As a result, abstract art was sent abroad in order to present a progressive view of Spain, while representational art was often analyzed for any political critiques. In this climate, the new realism ironically posed a threat usually reserved for the avant-garde. Yet, in spite of Spain’s exportation of abstract art, the country remained insular throughout this period, and Lopez and his circle were unaware of other contemporary realists like Lucian Freud and Edward Hopper.

The Mundane as Sacred

As Spain’s economy continued to grow throughout the 1960’s, a new consumer society began to emerge. While Pop artists in America had portrayed the influx of consumerism with a certain sense of irony, incorporating images from mass media and taking advantage of mechanical reproduction techniques, the Madrid realists portrayed this new urban landscape in quite the opposite way. For one, they avoided depicting the new modern conveniences that proliferated in society, choosing instead to paint everyday and common-place objects that were stripped of personal or emotional association; a clothes rack, a refrigerator, or a bathroom sink and mirror. In the context of Spanish art, this emphasis on everyday objects signified a break with the traditional still life Spanish painters like Ribera and Murillo who had painted more noble subject matter. At the same time, there was a break with more naturalist painters like Velazquez who had, on occasion, depicted ‘lower’ subject matter as in An old woman cooking eggs (figure 1). The distinction here is a matter of representation: Velazquez chose a common subject matter in order to draw attention to his abilities as a painter. An old woman cooking eggs is first a technical exercise picture as we are meant more to admire the artists skillful handling of the light reflected in the pestle and mortar than to peer into the psychology of the old woman. A subject matter of more importance might have inadvertently distracted the viewer from Velazquez’s power of depiction. The Madrid Realists, on the other hand, use their technical skill precisely to draw attention to common things. They strip their compositions of the superfluous, incorporating stark backgrounds and frontal elevated viewpoints. The effect is an almost clinical depiction of their subject matter, forcing the viewer’s gaze exclusively on the object. Lopez’ depiction of a refrigerator, both in Icebox (figure 2) and New Refrigerator (figure 3) are two such examples where Lopez reworks the classical genre of the still life. In both these paintings we find some of the traditional elements of the still life in the fruit, vegetables, and dead animal that are in the fridge yet they function here not to show Lopez’s skill as painter but rather to contrast the organic with the industrial. In doing so, the fridge goes from being an object not normally considered worthy of regard to a potent symbol of a society on the fringes of tradition and Modernism.

This emphasis on everyday objects has a certain allegiance to the German Neue- Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement of the 1920’s. This style also arose as a reaction to expressionism and non-representational models; in fact, many of its members had been former Dadaists. In 1925, the critic Franz Roh outlined the characteristics of this new style in his book ‘Nachexpressionismus- Magischer Realismus’ (Magic Realism: Post Expressionism), the main feature being a concern with the world of every day objects. According to Roh, it was through the overloading of the insignificant with significance that the metaphysical or ‘Magical’ qualities of the object were revealed. In his book, Roh put forth his vision for the new ‘Magischer Realismus’: “We are offered a new style that is thoroughly of this world, that celebrates the mundane.”2 Though Roh never gave a concise description ‘Magic Realism’ (a name which he eventually discarded for ‘New-Objectivity’), he did provide a list of characteristics and adjectives that defined this style and differentiated it from Expressionism: “Sober subjects…static… quiet…cold…an external purification of the object.”3 It is striking how well we can apply these to the work of Lopez and his circle. Today, the term “Magic Realism” in art has come to mean an interruption of the real world by the super natural. Ironically, it is under this definition and not Roh’s, which the Madrid Realists later became defined.

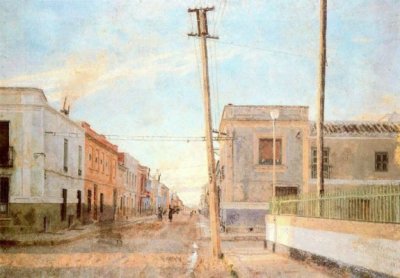

The subject matter the Madrid realists chose also came to represent the migrant experience which had defined Lopez’s generation. Spain’s shift from a primarily agrarian based economy to an industrial one in the 1960’s resulted in mass migration from rural to urban areas. The objects often represent the routines of a rural life that seems inconsistent with the new industrial society, the clash of old and modern world. They are the symbols of a liminal society where displaced people, bound by nostalgia for their old ways, exist on the fringes of the progress. For Lopez in particular, they are the artifacts of Tomelloso. The critic William Dyckes writes: “ It is a world of country people who moved to the city in hopes of improving their lot but never changed their ways: where life continues to unfold on a day-to-day basis, tile same tasks being carried out, the same events eternally recurring with imperceptible variation. Where women sew, cook, care for children, or sell chestnuts or lottery tickets in the street; where men work in small factories, ride crowded airless subways, talk soccer in neighborhood bars in the evening. Where people sleep in tiny rooms decorated with pictures of the Virgin, walk along unpaved streets that turn to dust in the heat of the summer, age quickly and fade. It is also the world where the Madrid realists have their homes and studios.”4 Dyckes might be describing Lopez’ early work where we find a nostalgia for a rapidly disappearing way of life. In Table near Tomelloso (figure 4) and Calle de Santa Rita (figure 5) painted two years later, there is a sense of community among the figures leisurely conversing with each other. Both show outdoor scenes bathed in late afternoon sun where man seems to co-exist with his environment. As well, all the objects on the table (grapes, a guitar, movie tickets, playing cards) speak of the traditions and pastimes of the region.

Both these paintings, which Lopez painted while he was living in Madrid, are very different in how he would depict the city years later. Atocha (Figure 6), refers to the train station in Madrid where Lopez first arrived from Tomelloso. It is painted almost entirely with somber grays, and there is a distinct shabbiness to the buildings. Unlike the Tomelloso scenes, the city is empty of people save for a couple fornicating on the street in the foreground. Their carnal display, in sharp contrast to the dignified and modest dress of the Tomelloso townspeople, is a stark reminder that real human contact is absent within the city.

This idea of alienation within urban centres is most evident in his cityscapes View of Madrid form Torres Blancas (Figure 7) and South Madrid (1965-85). Here, the city is depicted as an empty wasteland that speaks of the isolation of its displaced inhabitants. Nature and city (man and technology) appear incompatible with each other yet when we see how quickly the city is encroaching on the surrounding villages, we realize that man is also cut off from nature. Lopez also seems to recognize the presence of two incongruous elements of modernism: order and community with chaos and alienation. This is apparent in the claustrophobic and chaotic appearance of the city, an effect he achieved through his choice of an elevated viewpoint and with the presence of both run-down, shabby buildings and new buildings; a reminder that creation and decay are inseparable.

By the mid 1950’s to the early 60’s, Lopez began to incorporate supernatural elements into his paintings. Critics were quick to draw comparisons between Lopez and the literary tradition of Magic Realism, and soon the work of the Madrid realists fell within this category. In 1970, the Frankfurter Kunstkabinett in Germany gathered the work of the Madrid Realists for an exhibit entitled “Magic Realism in Spain today”. Yet, while this label might have helped critics categorize the work of the group and give them international exposure, it proved to be misleading because it failed to recognize some of the principle themes that were independent of the supernatural elements. Ironically, while most critics were prone to drawing false association with the Spanish surrealist movement that preceded them, as well as with the American magic realists of the 1940’s and 1950’s, few of them recognized in Lopez and his circle the elements of Franz Roh’s original concept of Magic Realism. Nevertheless, the surrealist elements in Lopez’ work are worth discussing because they represent an early pre-occupation with multiple planes of reality, a theme that he would continue to develop even after abandoning these elements.

Antonio Lopez Garcia’s multiple planes of Reality

When examining Lopez’s paintings from this period we either find supernatural elements intruding in the private moment within the lives of his subjects, or a juxtaposition of unrelated images within a work which create a sense of mystery. The Apparition (Figure 8) shows a small child mysteriously floating in space, being watched by a woman from the edge of the corridor. The child seems to be walking towards an open door where a couple lies sleeping in a bed. Lopez has divided this composition into three spatial planes, each occupied by a figure: the hallway on the left, the wall in the centre, and the bedroom visible from the open door on the right. These three spatial planes take on the significance of metaphysical states when they are paralleled with the three planes of reality in the work: the real, supernatural, and the dream world.

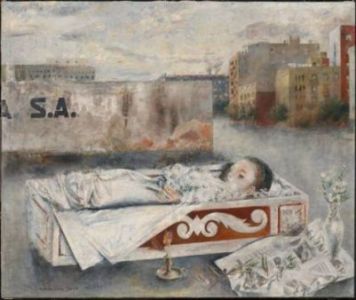

Dead Girl (Figure 9), another work from Lopez’s Magic Realist period, belongs to a group of paintings where private space and intimate moments are juxtaposed with public open space. Like Atocha, Lopez places a seemingly out-of-place image, a child in an open coffin, in an exterior urban setting. The surrealist elements here hint at a supernatural world beyond life and death. In both of these works, Lopez merges the intimate moments of his subjects with immense outer space therefore blurring the boundaries between the real and the unknown.

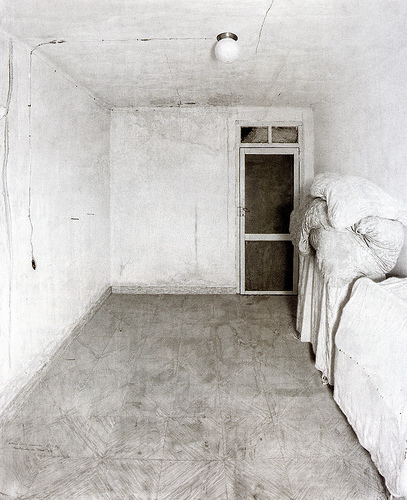

Eventually, Lopez would begin to depend less on supernatural elements and more on spatial tension to depict this hidden reality. This is most apparent in his drawings of sparsely filled rooms that are devoid of any personal or historical association. In Room in Tomelloso (figure 10) the feeling of absence in the room becomes the primary subject of the work and a meditation on silence and mystery. Door frames and open doors are motifs that Lopez had already begun to incorporate in some of his magic realist works such as The Apparition and here as well, they serve as symbols of transcendence. The sharp contrast between the size of spaces outside and beyond the door frames creates a spatial tension and impels us to be voyeurs in a psychological and literal sense.

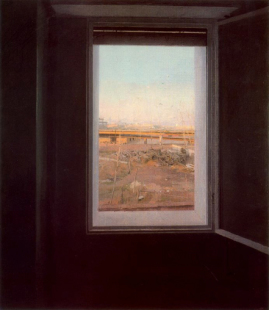

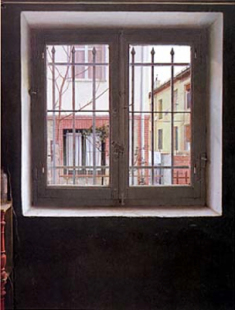

Lopez also uses exterior space as a symbol of the unknown and mysterious. The metaphor of the window had long been used in art and Lopez and Isabel Quintanilla both painted repeated versions of it (Figure 11-12), with Lopez executing at least seven different ones. In Window in the Afternoon, Lopez was compelled to paint the bright view from a window as seen from a dark room, creating a juxtaposition between the dark and claustrophobic interior, and bright infinite exterior. In this context, the glass represents the division between the inner and outer dimensions of man with Lopez suggesting that its transparency is an illusion of freedom. “Something happens when you look out from the inside”, Lopez says, “It’s not just another scene; there is something deeply and mysteriously moving about it…I imagine there’s also something psychological about it. It’ s like looking through a hole. Or like an animal peeking out from it’s burrow.”5

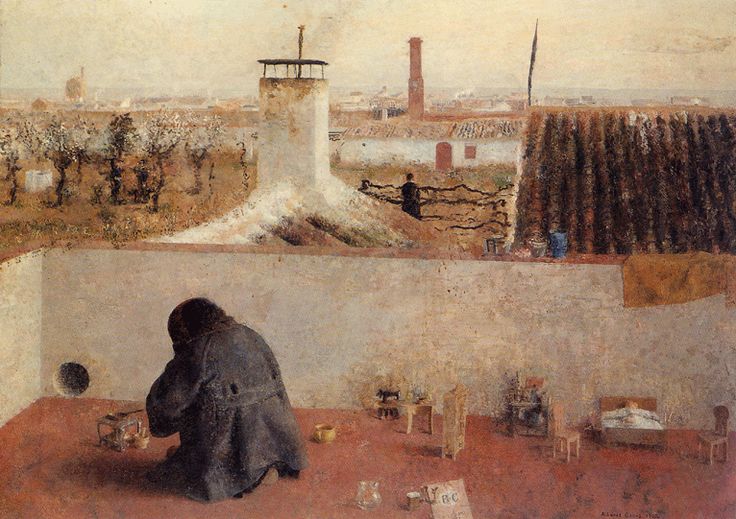

In other paintings from this period, Lopez incorporates an elevated visual axis on the same level as the horizon, allowing the viewer to see multiple planes simultaneously. By choosing an omnipotent viewpoint, Lopez reproduces the effect of the child suspended in space in The Apparition, suggesting a hidden world beyond that of his subjects. Of particular importance is Lopez’ use of layered planes that he divides by means of compositional elements; walls, houses, or variations in lighting. This slicing up of receding distances into two dimensional planes and layers harkens back to Braque and the Cubists who were concerned with what Braque called “a materialization of space”6. Even though Lopez does not geometricize his forms as the cubists did, he shares an affinity to them by questioning the boundaries of space and our relationship to it. One example of this is the painting Carmencita playing (figure 13) which shows a young girl on a balcony, arranging miniature furniture. She is depicted from an elevated viewpoint which allows us to see beyond the wall of the balcony; that is, beyond her familiar world. Thus, the balcony in this case functions much the same way as the window does: as an ontological observation point. The painting is divided, like The Apparition, into three spatial planes: the balcony, the garden and neighbouring houses, and the landscape that stretches to the horizon and merges with the sky. In turn, these three spatial planes correspond to three planes of reality: the imaginary world of the child depicted by the miniature furniture, the real world of the balcony, and the metaphysical world represented by the infinite horizon.

The use of multiple planes in Lopez’ work also raises questions of perception and urges a re-evaluation of the genre of Realism. The dilemma of the realist painter is that in his attempt to depict the three dimensional into two dimensions, he must rely on mathematical perspective to provide an approximate representation of the scene. Since a certain amount of illusion is required to hide perspective distortions that arise, one can say that a realist artist ‘creates’ a sense of reality. In Sink and Mirror (Figure 14) Lopez uses a neutral band at the centre to account for the visual distortion that he encountered by placing himself so close to his subject. We see two distinct view- points along a horizontal axis: the mirror straight on and the sink as if we were looking down. Lopez’ decision to not use a single perspective point to join both sections reflects his commitment to a true depiction of reality. In his view, perspective misrepresents reality by creating the illusion of spatial unity. In Toilet and Window (Figure 15)), Lopez continues to explore multiple view points only this time, he chooses two radically different views, using the neutral horizontal band as a spatial rather than corrective resource. He plays with spatial distance by bringing the frosted window closer to the viewer in the top frame than it would appear to us within the perspective of the bottom frame. This idea of using multiple view points, and re-arranging spatial planes is once again highly reminiscent of the work of the Cubists. Braque’s attitudes on perspective might well be applied to Lopez in this case, “The whole renaissance tradition is antipathetic to me. The hard-and-fast rules of perspective which it succeeded in imposing on art were a ghastly mistake which it has taken four centuries to redress: Cezanne and after him Picasso and myself can take a lot of credit for this. Scientific perspective is nothing but eye-fooling illusionism; it is simply a trick- a bad trick- which makes it impossible for an artist to convey full experience of space, since it forces the objects in a picture to disappear away from the beholder instead of bringing them within his reach, as painting should.” 7

The Eternity of the Ephemeral

A paradox exists within the genre of realism. On the one hand, it is concerned with a truthful depiction of its subject, yet by its very nature as a time-consuming and laborious style, it can never capture the fluctuations in its subject over time. This is obviously evident when painting a non-fixed subject, but even in depicting a fixed subject, the realist artist must contend with the constant changes in light. No one understood this better than the naturalist landscape painters of the 17th century like John Constable (1776-1837) who used broken brush strokes in order to mimic sparkling light; a technique which would later be taken up by Corot and the Impressionists. Monet himself was known to align several easels beside each other in order to follow the changing sun on his subject.

Realism, therefore, requires a certain amount of fiction in order to make the unstable world appear stable. The artist must ignore the passing of time and use memory, or for the modern realist photographs, to fill in the gaps of information.

Early in his career, Lopez had found it difficult to work from photographs specifically because of the lack of information about light and space. This complete dedication to recording the present is most evident in the 1992 film ‘The Quince Tree Sun’ by Spanish director and Lopez’s friend Victor Erice. The film is a meditation on the fleeting nature of time as we follow Antonio Lopez for three months in fall painting a quince tree in his backyard. We see him, in the manner of an engineer, making spatial co-ordinates with paint-marks placed on the fruit and calibrating the light. As the season progresses, Lopez ties back branches as they begin to sag with the weight of the fruit and erects a tent over the tree to protect it from the rains and finally abandons the painting by October, when the light becomes too erratic and the fruit begins to fall from the tree. Watching Lopez in action, we can’t help feeling there is a certain absurdity in the whole endeavor. To suggest, as some critics have, that he is concerned with taming nature’s instability is erroneous. Quite the contrary, In showing Lopez as he tries to capture nature in the course of it’s development, the film suggests that in order for art to be pure, it should exist in the present. As he tells some foreign visitors, “the best part is being close to the tree”. Like Henri Clouzot’s 1956 film ‘Le Mystére Picasso’ which through the use of a camera on one side of a translucent canvas captures the real time creation of an art work, we are encouraged to look at the process as the true nature of art. In doing so, notions of ‘finished’ and ‘unfinished’ becomes arbitrary. “I always try to reflect the present,” Lopez says, “This present perhaps contains the memory of the past, but the picture is the result of an extensive time span, always in the present. These links to the present are the sustenance of your own life, and the gaze of the present contains all that you are and know, including your history-even though you may not be conscious of it. 8

Lopez is known to delay the completion of his works for years; constantly adding and removing elements in the work during that time. This is due in part to his working methods as he works on several paintings at the same time, often putting one aside for years, and he considers a work finished only when he can no longer follow the change in his subjects. In The Dinner (Figure 16), Lopez depicts his family gathered around a table sharing a meal. The painting has an unfinished quality to it, yet if we view it as encapsulating various moments in time during the routine of eating, we realize that it is intentionally inconclusive. The rough painting of his daughter, the multiple planes of his wife’s head, and the inconsistency of the food placed on the table (there are both breakfast and dinner foods) are all a testament to the daily routine of eating that is constantly in transition. The photograph of the pink meat pasted onto the canvas beside the painted chewed bread, which Lopez admits was initially a temporary fill-in while figuring out the compositional elements (9), serves as a reversal of photography and painting. In the context of the multiple planes of time and space in the painting, the photograph seems impotent in its depiction of reality.

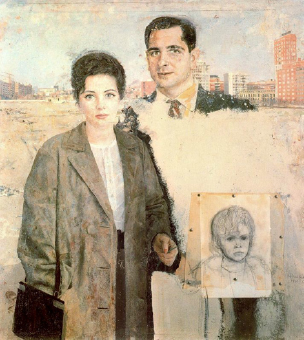

On a few occasions, Lopez has also used time as a narrative device, depicting the changes that occur in his subjects’ lives. Emilio and Angelines (Figure 17) was a commission for a married couple who, during the course of the painting, adopted a girl and then separated. Faced with this new events after having placed both of the figures, Lopez began by erasing the husband’s body to suggest an estrangement and later, tacking on a drawing of the little girl in his place. The drawing of the girl dated 1974, is a testament to the numbers of years Lopez devotes to a painting. At first glance, this painting also has an unfinished quality to it, yet when we use these unfinished traits (the erasing and pencil drawing) as narrative devices, we realize that it is deliberately unfinished. “The picture is never finished,” Lopez says, “It always remains open. You could go on, but difficulties would arise; weariness, other commitments and, above all, the wish to begin new works. So the picture, though unfinished, is halted at the moment.” (10)

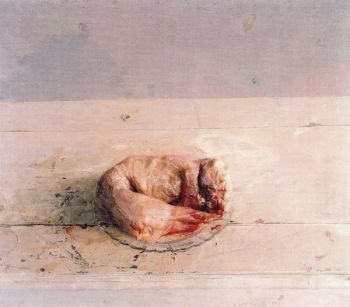

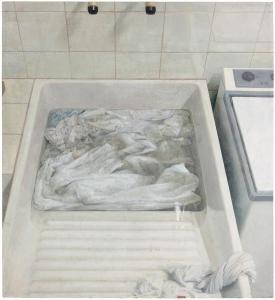

Just as Lopez uses spatial tension to represent multiple plains of reality, so too do we encounter a tension in his depiction of time. On the one hand, he is concerned with showing the passing of time in his work yet on the other, he actively pursues the theme of the ephemeral. Reality and the temporality of time are interwoven, representing the juxtaposition of the material, tactile world with the mysterious and ephemeral world. Lopez had already been exploring the theme of the ephemeral during his Magic-realist period through recurring motifs of candles, flowers, and fruit. The image of the lit candle suspended in air is probably his most well known motif from this time, and functions much in the same way as the apparitions that appear floating in space. Their fleeting nature, their association with disturbed slumber, and their capacity to illuminate, all evoke an awakening of consciousness. Even with the eventual stripping down of these symbols in his hyperrealist still-lifes a few years later, Lopez continues to choose subject matter that represents these suspended states of time. In Skinned Rabbit (figure 19) and Soaking Clothes (figure 20), Lopez chooses subjects that are between states of function. The rabbit’s objective depiction, denies any feelings of compassion or association, forcing us instead to focus on the silence and stillness of the scene.

By far the most potent symbol of the theme of suspended time is Lopez’ use of light which we see in his cityscapes Lucio’s balcony (1962-90) and View of Madrid from Torres Blancas (Figure 7). His preference for paintings at dawn or dusk when light is most unstable accounts for the amount of time he spends on a particular work and his limited output. Because the light is so unstable during this time, Lopez will paint for 15-30 minutes per session, only to set a painting aside until the next year once the season changes. The light of dawn and dusk represents for Lopez moments of dreaming, self-reflection and mystery. It is an ethereal light that reveals a new reality to its inhabitants, like the suspended candle and apparition. The lack of traffic or pedestrians, which Lopez admitted was a result of them passing too quickly through the artist’s field of vision, compliments this ethereal light. It has sent people inside, both literally and psychologically.

A comparison can be drawn here between Lopez and Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), a painter who he cites as an influence. With Vermeer, we also encounter an artist who was devoted to depicting reality as it appeared to him, for example in his of the use of a camera obscura in the place of mathematical perspective to represent three-dimensional space. The camera obscura was an early version of the plate camera though instead of the light falling on a sensitized plate, it was projected and then traced onto a canvas. In Vermeer’s work, there is also a tension between interior and exterior space depicted by the contrast between the closed-in corners of the rooms where he places his models and the infinite space suggested by the windows. The objects that regularly appear in Vermeer’s rooms, the maps and letters being read or written by the models, also allude to this outside world which is hidden from us by the oblique angle of the window. Lopez’ Mari en Embajadores (Figure 21) and Vermeer’s Woman with a Lute (figure 22), are two such works that encapsulate this tension between interior and exterior space. In both works, the female subjects glimpse from small openings onto the outside with apparent delight, suggesting an awakening of consciousness.

The most important similarity, however, is their treatment of light. For one, Vermeer and other Dutch painters of the late 17th century were the first to incorporate multiple light sources as they saw the interplay of diverse moments as a more truthful depiction of a reality than Chiaroscuro’s use of a single light source which had preceded them.

As well, Vermeer does not manipulate the light in his work, as many of his contemporaries did, but rather paints it as it appears. It enters obliquely from the window and falls on his characters, giving an almost celestial illumination to their everyday routines. As in Lopez’s work, light is inextricably linked with time. The light entering the room creates a stillness often associated with flash photography, having the effect of suspending the actions of his models. The critic John Berger writes, “The function of the closed room is to remind us of the infinite…(Vermeer) was able to convey with unique precision what constituted one moment because he was so keenly aware, objectively and without a trace of nostalgia, that each succeeding moment was unrepeatable.”(11) The fact that both these artists pursued the study of optical images, through the use of the camera obscura in Vermeer case and photographic reference early in Lopez’s career, suggests that they were both aware of the limits of depicting reality truthfully. It is perhaps out of this awareness that both Vermeer and Lopez chose to depict the “aspects of reality which by their nature defy visual representation.”(12)

In Lopez’s drawings of his interiors, we see this same revealing quality of light. The light reflected in the background of Studio with three doors (Figure 23) resembles an instantaneous photographic flash, which strips the scene of any emphasis. Nevertheless, the light shares the same probing and analytic function as in the work of Vermeer. We are voyeurs, looking at the scene not from behind a curtain, as in the work of Vermeer; but behind the light source that is positioned precisely at the position of the viewer. As in ‘The Apparition’, Lopez uses partially open doors to suggest three multiple of reality but this time he intersects this with a further three planes: the virtual space where the spotlight and painter are, the studio space in the foreground, and the unrevealed space of the two rooms in the back. The result is a complex, multi-layered study of time and space where reality and fantasy are blurred.

Although Lopez’s light here is artificial and cold compared to Vermeer’s warm and natural light, the effect they both have on the scene is the same. They force our gaze on the insignificant; the sparse depersonalized space in Lopez’ case, and the everyday routines of Vermeer’s characters. It allows us “to penetrate the deepest recesses of reality- to illuminate reality- to focus on its hidden truth where it is least perceptible.”(13) In this context, the lack of psychological insight, for which Vermeer’s work has often been criticized, has a close proximity to the purging of the personal and subjective which has come to define the work of Lopez.

The critic Robert Hughes described Lopez’s studio drawings as a “mesmerizing conjunction of opposites”. He writes, “On the one hand, the patient surface, rubbed and reworked to a silvery bloom punctuated with dark points of attention, anxiously tender and very seductive to the eye; on the other, a kind of silent rawness; a persistent undercurrent of anguish about the worth of what can be seen. It is the very reverse of academic art and the antithesis of illustration.”(14) This conjunction of opposites has been at the forefront of his work from the beginning, and although Lopez has expressed it in different ways throughout his career, the motivation has always been the same: to express the metaphysical essence of his subject. The ‘silent rawness’ which Hughes refers to is precisely the confronting of this essence, a state of being which can only reveal itself to the viewer once the artist has purged the work of any anecdotal or personal association. The seemingly incompatible qualities of his work; the precise, labor-intensive technique and the mundane, depersonalized subject matter can be confusing if one continues to think of realist painting as a representation of material nature. Yet, if we look beyond this material nature, we realize that Lopez has given us a new realism: one that scrutinizes reality in order to show that which is immaterial, unstable, and supposedly inexpressible.

© Roberto Rosenman, 2013

Notes

1 Berger, (2001) p.124

2 Roh, p.15-32

3 Roh p. 15-32

4 Dyckes, (1973), p.

5 Fernandez-Cid, (2006), p.119.

6 Miller, (2001), p. 133.

7 Ibid p. 97

8 Lopez, Quoted in Brenson, “Interview”, 315.

9 Kassan, from his website: http://www.davidkassan.com/on-painting-antonio-lopez-garcia/

10 Lopez, Quoted in Brenson, “Interview”, 337

11 Berger, (2001) p.124

12 Ibid, 124

13 Serraller, (1990), p. 45.

14 Hughes, (1986) p. 127

Bibliography

Berger, John. “The Painter in his Studio – Vermeer” Selected Essays. ed. Geoff Dyer London: Bloomsbury, 2001.

Brenson, Michael. “Interview by Michael Brenson with Antonio Lopez Garcia,” in Antonio Lopez Garcia, ed. Michael Brenson, New York: Rizzoli Interational, 1990.

Berger, Laurel. “The Spirit of the Quince Tree” ARTnews v29 (November 1993), pp 101- 102

Brutvan, Cheryl. Antonio Lopez Garcia. Boston: MFA Publications, 2008.

Dyckes, William. “The New Spanish Realists” Art International Magazine, (September 1973), pp

Fernandez-Cid, Miguel. The Masterworks. Translated by Virginia Pugh Hernandez, Barcelona: Ciro Ediciones, 2006.

Garcia, Angeles. “I Haven’t decided what my life is” El Pais. Translated by Roberto Rosenman. (March 4, 2008)

Ghent, Henri. “Spanish Art in Transition” Art International v19 (October 1975) pp 15- 22.

Hughes, Robert. “The Truth in Details: A rare show by the peerless realist Antonio Lopez Garcia” Time Magazine (April 21, 1986) pg. 127

Kassan, David. “ARTISTS ON ART – ON PAINTING ANTONIO LOPEZ GARCIA”, from his website: http://www.davidkassan.com/on-painting-antonio-lopez-garcia/

Kozloff, Max. “Antonio Lopez: Painter of Madrid” Art in America v81 (October 1993) pp 94-101

Michalski, Sergusz. New Objectivity- Painting in Germany in the 1920’s Koln: Benedikt Taschen Verlag, 2003.

Miller, Arthur I. Einstein/ Picasso- Space, Time, and the Beauty that Causes Havoc. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Roh, Franz. Nach-Expressionismus. Magischer Realismus. Probleme der neuesten europäischen Malerei. Leipzig: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1925.

Serraller, Francisco Calvo. “Enlightened Reality: The Paintings and Drawings of Antonio Lopez Garcia”, Antonio Lopez Garcia. ed. Michael Brenson. New York: Rizzoli International, 1990.

Stolz, George. “Madrid: Clash of the Titans,” ARTnews, v.92 (September 1993)